Evidence-Based Practice Is a Process

By: Monica Faulkner, Ph.D. & LMSW & Danielle Parrish, Ph.D.

| Important to Know:

|

We all want to do what is best for our clients. The best thing should always involve grounding our practice in the best research evidence we have on how to meet our client’s specific needs. Unfortunately, discussions about evidence-based practice often devolve into evidence-based chaos.

Policymakers and funding agencies are demanding certain percentages of programs be “evidence-based,” judges may only refer to “evidence-based” programs, agencies are desperately trying to figure out how to afford evidence-based practices and practitioners fight battles to adapt evidence-based models so that it works for their clients. If we truly understood evidence-based practice as a process, this chaos would not be negatively impacting our practices, policies and agency decisions.

In fairness to practitioners and policymakers, many academics who have driven discussions of evidence-based practice have done a poor job of using a common definition. In some cases, academics have referred to evidence-based practice as using a model that has been deemed “evidence-based” after being tested through a randomized controlled trial or equivalent research design. When we have individual models that we designate as evidence-based, we create chaos because we assume that the same intervention or program will work for everyone regardless of their culture, values and preferences. We also assume that we can bring the “evidence-based” program or intervention to full scale without taking proper stock of the cost, resources and training required.

Consequently, this definition can contribute to the evidence-based chaos by misrepresenting the true intentions of the original evidence-based practice model, which highlighted the importance of integrating the best available research with the client’s background, culture and preferences, as well as professional practice expertise. The consequences of this chaos can include wasted time and money, potentially lower levels of client engagement, partially implemented programs and clients who do not receive the very best services.

Who Decides What is Evidence?

First, we need to understand who decides something is evidence-based. In the case of teen pregnancy prevention, the federal government has created a list of evidence-based programs with the input of research think tanks. Most people assumed that the evidence behind these programs was that they reduced teen pregnancy. However, because preventing teen pregnancy takes years to study, most of the programs only had evidence that impacted short-term outcomes like increased knowledge about prevention or increased intention to not engage in sexual activity. These outcomes do not necessarily lead to changes in risky behavior.

To be considered evidence-based at this time, a program needed to show a statistically significant change in just one short-term outcome. Statistical change, alone, tells us if those who got the intervention improved more than the comparison group, but provides no information on the degree of difference. When we know how different they are, we can better discern if an intervention is likely to result in meaningful change for our clients. As discussed below, this is an important consideration when selecting an evidence-based program. To be fair, these determinations make sense, as most research has not been adequately funded to collect long-term outcomes and this research is only emerging.

However, once something is designated evidence-based, the social services field is inclined not to question the research behind the evidence. New research evidence is always changing and emerging, and should be considered periodically to ensure best practice. As we learned from years of funding abstinence-only sex education, we may know better, and can do better, when we take this research into consideration.

Who Controls Access to Evidence-based Programming

When we designate something as evidence-based, it often becomes a “golden ticket.” Programs that have invested time and money to create an evidence-based practice, now have ownership and control over intellectual property that often must be purchased by others. Funders who require grantees to use these practices are essentially requiring programs to spend potentially thousands of dollars in purchases and trainings. In many cases, grantees benefit from high-quality tools and information. However, they can also struggle to keep their staff trained when there is turnover or when they can no longer afford to purchase licenses and trainings.

As funders and practitioners, it is essential to adequately budget for training, implementation and sustainability costs when requiring evidence-based programming. Likewise, funding sources and practitioners may want to also assess the cost-effectiveness of various approaches, as some programs offer many of their materials and trainings for much lower costs than others.

But What if the Evidence Doesn’t Match the Need of the Client?

The most chaotic factor in our use of some evidence-based practice is that the models and curricula may not match what our clinical judgment tells us is the best fit for our clients and we may have little means to adapt. Anyone using an evidence-based model typically has to implement the model with fidelity, meaning that any modifications have to be approved. In some cases, fidelity allows tailoring aspects of the intervention while maintaining the primary components of the intervention. In other cases, it means reading a script word for word during a home visit. Or it may be presenting sexual health content without the ability to modify that content for youth who have likely experienced sexual abuse. Our professional expertise should not be put aside because an evidence-based model requires a rigid approach to client interaction. When we “start where a client is”, we have to adapt and use our clinical skills in order to practice ethically.

Getting Out of the Chaos by Getting Back to The Process

The way we are approaching evidence-based practice has created chaos around what evidence is, the lack of accessibility to use evidence-based models and lack of ability to use our clinical knowledge in ways that benefit our clients. The good news is we can pull ourselves out of this chaos by using the originally intended definition of evidence-based practice. Instead of only accepting individual practice models or curricula as evidence-based, the field should utilize the evidence-based process.

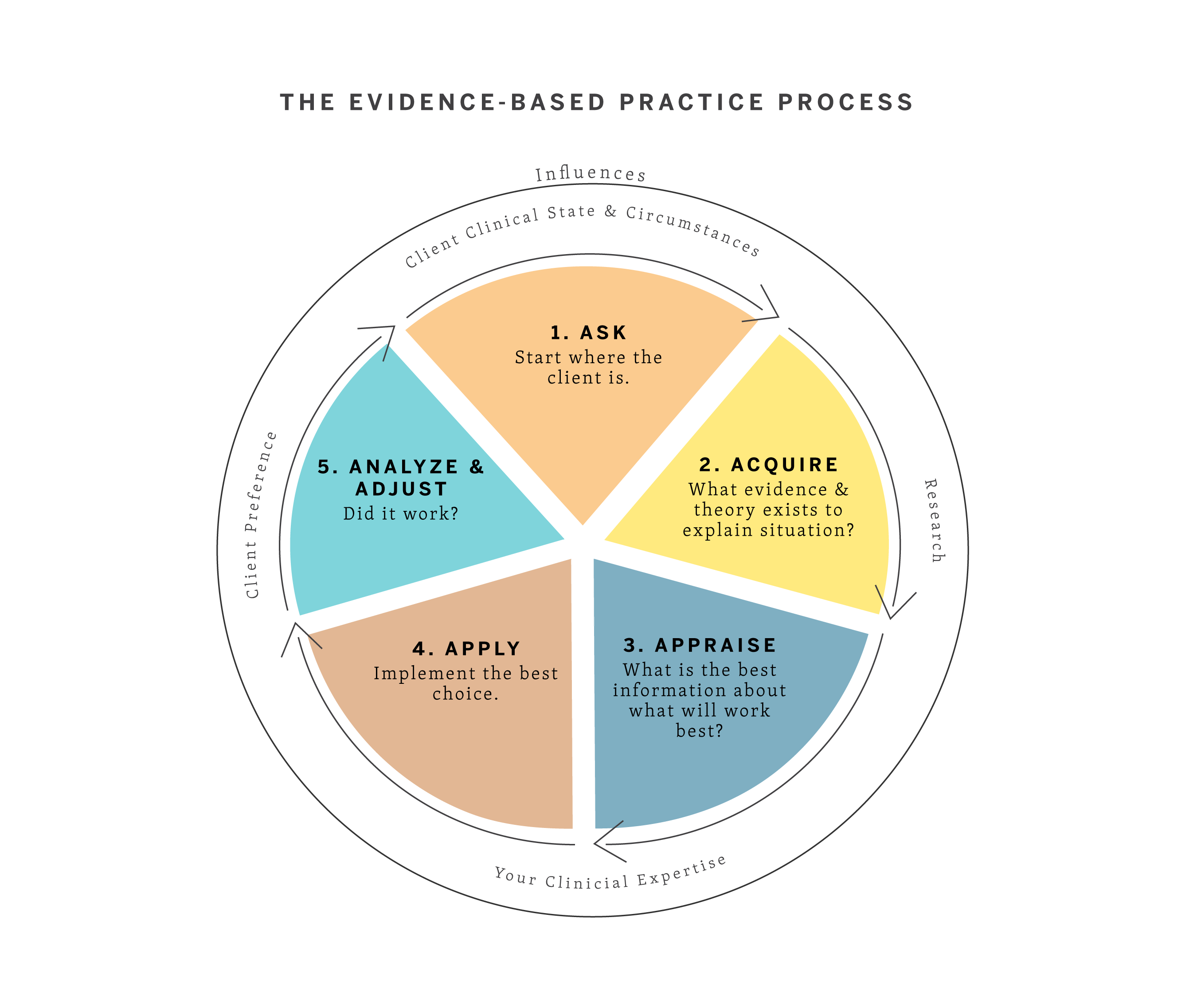

In clinical practice, an evidence-based process means we integrate the best research available with our clinical expertise related to our client’s history, preferences and culture. The National Association of Social Workers defines this process as: “creating an answerable question based on a client or organizational need, locating the best available evidence to answer the question, evaluating the quality of the evidence as well as its applicability, applying the evidence, and evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of the solution.” For social work, the process should include research evidence, clinical state of the client, your clinical expertise and the client’s preferences. In this process, there is no assumption that your expertise or the research evidence is more important than the client’s preferences. Most commonly, the process is characterized with 5 steps: ask, acquire, appraise, apply and assess. Combining this process with the Haynes et al. model of decision-making, social workers can utilize this simple guide for evidence-based practice.

The first step is to ask. Although this step seems obvious, far too often experts come into treatment and communities assuming they know what is best. Communities may have a model funded and they attempt to serve everyone with the same model. A core social work value is that we assume the individual or community is the expert on their experience. If you are working with an individual, this is the point where you ask questions like: What brought you in for services? What do you hope will get better? How do the people around you view treatment? What does your support network look like? If working with a community to roll out an intervention, the ask is critical. You need to know what the community values, what the community wants, what has or has not worked before and what the strengths of the community are.

After you know the needs, you acquire information. This is the point where you look at the research evidence. Is there a practice model that fits with what the client or community wants and their background characteristics or culture? What is the research that has been done to show that model works? Is it of good quality?

After you find information, you appraise it because we know one size never fits all. You should be asking questions about the theory behind a particular intervention, cultural relevancy for your client, generalizability of samples and expected outcomes. When thinking about outcomes, which seem most meaningful? Do the outcomes in the study suggest that there is clinically significant change? This means, does the change in outcome reflect what you, as a practitioner, would like to see in terms of improvement from your client? This is important, as a study can show significant differences between an intervention group and a control group, even if the intervention group only improves just slightly and stays below a meaning clinical cutoff score (e.g., for depression). Most likely, the intervention you found will also need some modifications and it’s important to assess the degree to which such modifications can be made while achieving similar outcomes.

The next step is to apply the intervention. To do this, you consult with the client. Explain what resources and options you have found, including the limitations and expected outcomes. Part of informed consent should include what you found (or did not) in the research. Then together you decide how to proceed. This is essential to empower and engage the client in the helping process.

The final step is to assess how the intervention worked. In order to build evidence for your future practice, you should utilize a single subject design so that you monitor progress with your client. If shared with the client, these graphs of outcomes over time can serve as a useful tool, highlighting changes that may suggest a need for clinical attention during a specific week, or for changing the intervention approach altogether. The importance of such evaluation is highlighted by the fact that just because there is good research evidence for an intervention does not mean the intervention will work for everyone. For example, a randomized controlled trial may suggest that 80% get better in an intervention group compared to only 20% in a control group. Your client could be similar to the 20% that did not get better in the intervention group, in which case, an alternative approach may be needed. For a community intervention, program evaluation should be utilized to help build evidence for future practitioners and inform needs to improve implementation and fidelity.

Process Matters

The confusion and chaos around evidence can improve if we change our language and our understanding of what evidence-based practice is. As practitioners, we have to be speaking with our clients, policymakers, agencies and funders about evidence-based practice as a process. Be prepared to explain how evidence derives from research, from the client’s situation, from the client’s perspective and from your expertise. Help present and advocate for alternative programs that take all of these factors into account by learning and utilizing the evidence-based practice (EBP) process. When we only rely on research and fail to take context and client factors into consideration, we fail to use and build evidence appropriately.

Additional Reading:

For practitioners hoping to learn more about the EBP Process, here is a useful online training resource: Evidence-Based Behavioral Practice: https://ebbp.org/

Drisko, J.W. & Grady, M.D. (2015). Evidence-based practice in social work: A contemporary perspective. Journal of Clinical Social Work, 43, 274-282.

Evidence-based practice in psychology. (2006). American Psychologist, 61(4), 271-285. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271.

Haynes, R., Deverwaux, P. & Guyatt, G. (2002). Clinical expertise in the era of evidence-based medicine and patient choice. Evidence-based Medicine, 7, 36-38.

National Association of Social Workers. (2010). Evidence-based practice for social workers. Washington DC: author.

Parrish, D. (2018). Evidence-based practice: A common definition matters. Journal of Social Work Education.

Spring, B. & Hitchcock, K. (2009) Evidence-based practice in psychology. In I.B. Weiner & W.E. Craighead (Eds.) Corsini’s Encyclopedia of Psychology, 4th edition (pp. 603-607). New York:Wiley.