Measuring Burnout in the Context of Something Greater Than the Self

A Project HOPES Evaluation Case Study

By Allie Long

As we look deeper into the ways that staff burnout has affected the field of social work this month, we realized something interesting about its connection between research and practice. That is, as the public perception of burnout shifts, so too does our ability to measure it.

As we look deeper into the ways that staff burnout has affected the field of social work this month, we realized something interesting about its connection between research and practice. That is, as the public perception of burnout shifts, so too does our ability to measure it.

The Backstory Behind Burnout

Traditionally, the concept of burnout was viewed as a solitary concern of the individual rather than a problem related to various factors, including one’s environment. After Freudenberger coined the term “burnout” in 1975, most burnout measurement scales for the next decade were structured to reflect this individual focus. More recently, however, there’s been a shift in perception among researchers and the study of burnout. Contemporary literature has shifted towards a theoretical structure of burnout as it relates to organizational sources of stress. In other words: helping professionals are most likely not experiencing burnout as an individual, isolated incident.

In 2007, Lee et al. published a new measurement tool that uniquely took into consideration the interaction between environmental and organizational factors that might inherently affect a helping professional’s level of burnout. This tool is called the Counselor Burnout Inventory (CBI), which is a 16-item measure that is broken into five subscales, with questions about exhaustion, incompetence, negative work environment, devaluing client, and deterioration of personal life.

The Analysis of Burnout in TXICFW Data Collection: A Case Study Example

In our 2016 evaluation report of Project HOPES, we utilized the CBI as a means to better understand burnout among direct service staff who are implementing evidence-based parent education programming to families. HOPES stands for Healthy Outcomes through Prevention and Early Support, which is a child maltreatment prevention program run by the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services, Prevention and Early Intervention Division.

For the last several years, Project HOPES has been working to address the prevention of child abuse and neglect by focusing on community collaboration and evidence-based programming for families in high-risk communities. In so doing, Project HOPES is aiming to increase the safety, stability, and nurturing factors in a child’s environment which has been shown to reduce the likelihood of childhood abuse.

It is well known that staff burnout is a problem within this field, but it also affects the stability within a family’s environment. When clients are meeting new case workers or home visitors, building trust and rapport may become increasingly difficult if they have the experience of their source of support only staying for a short while. In order to capture the nuances of staff turnover and essentially the success of HOPES we asked about burnout in our FY16-18 evaluation.

The 2016 evaluation report was multifaceted in its evaluation and findings. While it was not an evaluation report devoted solely to professional burnout, this was an important factor considered when analyzing the success and challenges faced by direct service staff administering the HOPES program.

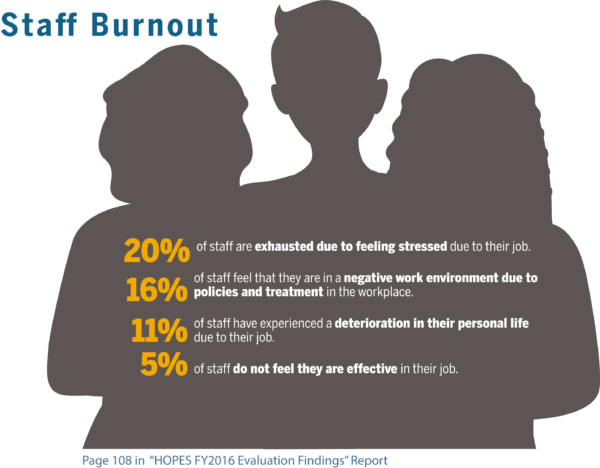

Researchers found that among the 107 HOPES staff surveyed, there was minimal burnout reported. Instead, the areas most highly ranked by staff were related to exhaustion (20%) and professional policies or procedures that could contribute to a negative workplace environment (16%). Although this could be due to a variety of reasons, one participant suggested that the team’s ability to create boundaries was a crucial factor in preventing burnout:

While setting boundaries might seem like a personal skill that a professional must learn to do for themselves, making boundary setting a part of the organizational culture could more adequately address the environmental factors that lead to burnout.

Take Aways

The acknowledgement of burnout is not only important when talking about helping professions—it’s necessary. What’s more: burnout does not exist in a vacuum, nor is it any individual’s “fault” for feeling it. We felt it was essential to ask about staff burnout in our evaluation of the HOPES program. By addressing burnout within the context of a larger analysis, the HOPES report serves as a vital reminder that we are all impacted by a variety of influences, which in turn affect us each differently. As we continue to learn more about what contributes to burnout, so too will our research and practice evolve to take these nuances into account.